Lately I have went through a rather extensive amount of research and writings on right-wing movements in Europe, fascist political parties and how they during the last decade have not only entered several national parliaments, but etablished themselves in these parliaments (on both regional and national level). One of the latest example is the national election in Czech where the two right-wing populist parties ANO and Usvit were given increased support and influence in parliament.

This emerging trend, even if trend perhaps is the wrong term since it has been evident for several years, has often been approached through discussions on who is voting for these parties rather than understanding the mechanisms creating the political discourse that legimitize these parties and movements. Here I would like to emphasize two, in my opinion fundamental, dimensions in a potential explanatory model. And these are just two things (out of so many other) to remember when thinking about or discussing this topic.

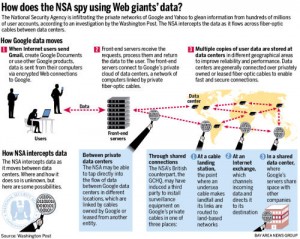

1/ Right-wing extremist parties and movements early adopted Internet as a vital mean for gaining support.

The literature and research on this subject rather cohesively suggest that for the extreme right, Internet is perhaps the most important tool for gaining support. Seldom do for example left-wing movements, utopian communist agendas or Marxist ideologists share the same strategic use and widespread attention in relation to Internet. Of course it helps that Internet provides the opportunity for anonymity, making it easier to express opinions that is far more tabu in present democratic society than for example opinions supporting the ideas of Marx or Lenin (given present the political climate in Europe). It is not to far fetched to claim that several right-wing parties to a large extent has managed to reach support among demographic groups that they never would have been able to if it wasn’t for Internet and new media technologies. And one shoud remember that during the 1990’s, a time when the extreme right was starting to grow substantially, these organizations were often excluded from mainstream media and were forced to use alternative media to reach people. Hence, few arguments would suggest that it would be better to silence these voices.

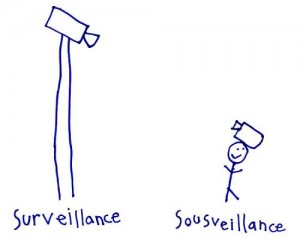

2/ Contemporary media- and political discourse around Europe emphasizes conflict rather than consensus.

Even though mainstream media seem to have a problem with highlighting immigration policy in a balanced way (often it results in dichotomies of good vs bad), this dimension involves much more than media logic. When studying how news media frames certain questions it is easy to outline specific news values and structures that dominates. Conflict is for example much more interesting for an audience than consensus (and some news media can create conflicts in a report about an empty room). And since political parties need the mainstream media as much as the media need political parties, a discoursive cooperation evolves. In the same way as Richard Jackson argued for how our perception and talk around the war on terrorism were creted in an interplay between news media/journalists, politicians, legislators and ordinary citizens – we can assume that the way we think and talk about both immigration and multiculturalism as well as the right-wing movements themselves, is constituted by a similar interplay. The words we use, the concepts news media use, the angles and framing of these issues – all result in a specific way of thinking.

And when several factors in this demand a simplification of the world and of complex questions, our perception is also simplified and neglects important and rather basic moral dimensions of human behaviour, of humanity and acceptance. The spiral we are in, where we tend to observe an extremely rapid growth of right-wing parties and ideological ideals based on not seldom homophobia, racism, islamophobia and fear become an increasingly legimitized political discourse, must be challenged in a more profound way than what is happening. The responsibility is with politicians, with journalists and with strong opinion makers. And above all with ourselves.

Enlighten your children, work intensively in elementary education, scrutinize mainstream journalism and challenge what appear as natural. Never be afraid to raise a voice against this development. Not even if strange and unpleasant emails may appear in your inbox.

Never ignore the fact that Europe today is highly influenced by thoughts rooted in fascism and nazism.

I wish that last sentence sounded exaggerated.