Just returned after a visit to Philadelphia and participation at an international symposium on “Mediating Islamic State”, at the Center for Advanced Research in Global Communication at Annenberg School of Communication. It gathered researchers from different continents and countries and presentations and discussions generated truly interesting insights in the rich tapestry of perspectives applied (and needed) in the scholarly approaches to understand IS mediation. I will write a longer summary of the conference later on, as well as post links to all presentations. Stay tuned.

Monitoring Islamic State Telegram strategies

Thought it would be a good idea to update this blog slightly more frequent than every other 6 months, and maybe do shorter posts and try to communicate the ongoing work I do. Results and arguments from the research are and will mainly be presented in upcoming publications. Instead I will use this blog outlet as more of an update-platform where I simply provide some short information on the progression of my work with Islamic State (IS) propaganda (like an extension of my Twitter-feed).

So since early June, for almost four months now, I have been monitoring and tracking around 60 channels/chats/groups on Telegram, connected to IS. Now, this connection can be more or less obvious, but I have focused on those accounts that are clearly affiliated in terms of content being distributed (and a few other characteristics as well). After a few years of experience of daily collecting propaganda, I know quite well what is IS content and what is not, what is official and what is un-official/supporters propaganda.

The official channels (mainly Arabic channels of Nashir and Amaq News Agency) are constant in their presence on Telegram, in the sense that several replicas are running simultaneously, generating new channels after a few days in order to prevent being diminished in number by censorship. And once having been invited to these channels, it has been rather easy staying on and monitor the activity and content being spread through them. Certain skills in Arabic and jihadist terminology is essential for me, otherwise I would loose track rather fast.

The supporters channel are more problematic, as the ones I follow are frequently moving around, sometimes a couple of times per day. But so far I have managed to keep track of movements, get into groups and channels, only to reach my purpose to collect enough data/material of IS Telegram activities and content for empirical analysis meant for both ongoing book project and journal articles.

As co-editor of a new anthology on the media world and virtual universe of IS (script with peer-reviewer and publisher currently), I now also continued to write a monography in Swedish on the same topic, hoping to get published 2018. In the latter I will include IS move from Twitter to Telegram and extensively dissect the function of this platform and the media practices IS are utilizing.

So my research time (basically every evening) is spent on this currently, average 4-5 hours every day monitoring, taking screen-shots, downloading material etc – all in all to get a significant understanding of IS use of Telegram, from a propaganda perspective. Considering the difficulties of entering these channels and forums, I believe I am starting to get a really unique set of data and insight into one of the most complex and decentralised communication strategies of any terrorist organization in history so far.

All the brutality aside.

Barcelona attack? It will get even worse

As the attacks in Barcelona continue to evolve, yet to show the full extent of the horrific actions, some reflections can and should be made. Not necessarily about the perpetrators or a potential organisation behind it (ISIS not surprisingly claimed the attack only a few hours later), but about how we perceive these type of now re-occuring vehicle attacks.

Monitoring and following ISIS official as well as supporter-based propaganda leads me to believe we have legitimate reasons for concerns regarding the imminent future. Outrage and shock seem to dominate headlines around Europe this morning, and rightly so. However the vehicle attacks are first of all nothing new, and second of all a predictable tactic. There is no point in continously repeating academics, terrorist experts and security services who collectively have emphasised that these type of attacks are inspired in the propaganda, they are convenient and ‘easy’ to execute as well as causing severe civilian damage and hugh number of casualties – hence a suitable mean for achieving a certain purpose.

What on the other hand slightly surprises me, is the somewhat naive approach to this type of method. And I don’t refer to naivety regarding preventive measures (which are taken in many larger cities to minimise the risk for these type of attacks), but to what seems to be a general common notion about how these networks and individuals can be so cruel, so cowardly causing pain and suffering among innocent civilians.

Let me make it clear, it IS extremely cruel and all respect to victims and families around them, but from a larger perspective on the method for achieving their purposes, jihadist groups in general, and ISIS in particular, have for years exhibited a toolbox of methods and means to incite fear and suffering among their enemies.

All suffering is painful, all methods for causing it are despicable. But after having followed ISIS for years, knowing about their total disrespect for human life, their extreme and horrendous methods for killing those who they believe deserve it, and understanding the role of the propaganda in this – I see strong incentives for an escalation of not only killings and attacks, but for the designated methods of cruelty as well. Why?

Because they are not only throwing people off rooftops. Nor are they simply beheading kidnapped prisoners.

They are burning people alive in cages.

They rape, trade and kill women and their daughters.

They take pride in slowly sawing off heads from both alive and dead people.

They drown young men.

They mutilate their corpses.

They let prisoners run only to shoot them from a distance like a stray animal.

They cut off hands from teenagers.

They crush prisoners heads with rocks.

They train and let children execute.

The list just goes on.

And everything is being documented, filmed and photographed. Packaged and circulated. Often conveyed as retaliation or response to their own suffering. I have lost count of how many bodies and faces of dead children I have seen in the narrative of videos leading up to and used to justify behandlings and other methods.

These methods have marketing values, some of them have religious connotations for ISIS (beheadings for instance), some are designed to provoke, some are designed as retaliation or for strengthening the in-group identity, and some are just convenient. But the plethora of methods also speaks volume about how ISIS see the world, through history, today and from here on.

The vehicle attacks around Europe, inspired or directed, are perceived as shocking since few people know the extent and range of torture and cruelty present in ISIS ideology and actions every, single, day.

“There is no action without reaction”, is a commonly used phrase in pro-IS forums. Imagine that videos of attacks and of executions circulate all the time in hundreds of these forums, feeding and bolstering hatred towards their enemies, numbs their supporters sense and respect for human life and suffering. Of course there will be supporters who finally decides to take action. By choosing methods that are not only convenient. Filled with so much hate and conviction, knowing you will die yourself, do you really think they will stop and think about the suffering of others?

With all respect to victims of attacks in London, Paris, Manchester, Barcelona – these attacks are not surprising, and they will most certainly get even more deadly, and designed to cause as much suffering as possible. Not only in terms of casualties.

Because the boundaries between reality and fiction, between life and death, have for years been systematically blurred by an organisation like ISIS and through their propaganda.

And I don’t see why their supporters around the world would suddenly start feeling respect for the life of others.

ISIS schools and indoctrination of children

Recently I attended and presented at a Nordic conference dealing with radicalisation and countering violent extremism. There were several interesting talks by researchers from a wide array of intellectual disciplines, including for instance political science, sociology, anthropology, media studies, history and educational studies. The variety of perspectives is something I have continuously cherished as I find interdisciplinary approaches to be a necessity to tackle extremism and radicalisation. Not only did I emphasize this need in my talk, but I also tried to highlight the importance of expanding the understanding of online- and other media practices when dealing with the hard defined concept of radicalisation. Grasping the significance of media propaganda and virtual interaction in the process of developing radical ideas and support for extremist ideologies, is still a challenge that neither the research community or political incentives have managed to approach in a sufficient way. We still don’t know how the sophisticated Information Operations of the Islamic State actually appeals to and resonate with the individual or the collective ideologically likeminded. And to be honest the research community still struggles to understand the often neglected offline ideological strategies which in fact are very prominent and important when approaching the hybridized warfare of the Islamic State. There are obvious reasons for this in terms of the (im)possibilities to ethnographically or anthropologically approach members or supporters of Islamic State’s world view, difficulties of interviewing defectors or identify individuals in the initial stages of radicalisation. We can, and should, discuss how the organization successfully has managed to amplify pull- and push factors, to inspire both cognitive and behavioural dimensions of radicalisation, and to attract more supporters on a global scale than any other contemporary terrorist organization. In order to do so we need not only this just mentioned closer interdisciplinary approach, but also recognize and identify long-term risks and threats to society, especially considering the currently increased outsourcing and spread of salafi-jihadist terrorism.

Perhaps the most significant entrance point to such a discussion is the educational system of the Islamic State, how the indoctrination of children, both in classrooms as well as through digital tools, is performed in order to prepare them for being on the frontline of the next and future generation of jihadists – let’s allow ourselves to call them ‘Islamic State 2.0’. In order for societies to deal with the fact that a huge amount of children that lives, or have lived, under Islamic State control in the near future can be mobilizing, be outspread, establishing new networks and affiliations or simply act as lone-wolfs – there is a desperate need to get a grip of what they have went through, what they have learned from a young age and how the indoctrination processes actually looks, both through digital means and offline ideological measures.

I think we are many who would agree that an increasing concern when it comes to the capabilities of the Islamic State, is the systematic use of children in propaganda and recruitment efforts as well as in military operations and executions. From a media perspective the most interesting is perhaps the depiction of children in the propaganda; how they are portrayed, in what roles and the rhetorical appeals connected to these portrayals. But the nowadays extensive use of children in the messaging is also a lens through which we can obtain broader sociological insights about what characterizes the evident indoctrination process within the Caliphate and the role of children (boys are usually referred to as ‘cubs’ and girls as ‘pearls’ or ‘flowers’) in the social structure of the Islamic State.

Of course the strategic use of children in both propaganda and military operations is nothing exclusive for Islamic State. Other contemporary groups both have applied this and unfortunately still does it, although previously mostly related to child soldiers and organizations like al-Qa’ida and Boko Haram are still prominent in this matter. But what separates the Islamic State seems to be the systematic efforts of indoctrination and making children a cornerstone in the future of the organization and by definition, in the self-declared state project. It is also a separation from other groups when they’re ideologically justifying child-rearing in much of the propaganda, and they have strong media enterprises behind them enhancing this strategy.

In relation to the state structure it gives this justification a stronger emphasis through the fact that there is a Ministry of Education (Diwan al-Ta’aleem) implementing the ideology at full force. And this aspect is rarely highlighted in mainstream media reports about Islamic State’s use of children. Rather the focus, for obvious reasons, is aimed at the propaganda content depicting children used in the most brutal of narratives: as eulogised suicide bombers, executioners in beheadings and/or as part of firing-squads, which generates better headlines and corresponds with the contemporary news logic feeding the simplified image of the organization as solely a brutal death cult.

However this does not take away that the social structure and institutions of the Islamic State, even if they currently are struggling to keep the societal formation together, are strongly and since long deliberately rooted as backbones of this organization. Boys between the age of 6-18 and girls usually between 6-15 (as girls who are married are not in school) have to take part of mandatory education, from the age of 6 in separate classes depending on gender. Not all of the foreign recruits or parents within the local population obey the enforced obligation and instead choose to keep their children at the house, although a considerable amount of children living inside the Islamic State do attend. For the local population the significant changes of the curriculum since the Islamic State took control of the area, are evident, as strict interpretations of Islam and salafi-jihadist ideology is being extensively tought. Any teacher who deviates from the curriculum risks being executed.

Depending on where the children come from there is also a division made (you never see children from the Caucasus or parts of Europe in the same class as children from a remote Sunni tribe in Syria, for instance). The foreign recruits receive extra classes in Arabic, just as they are offered instructions in English to speed up the education.

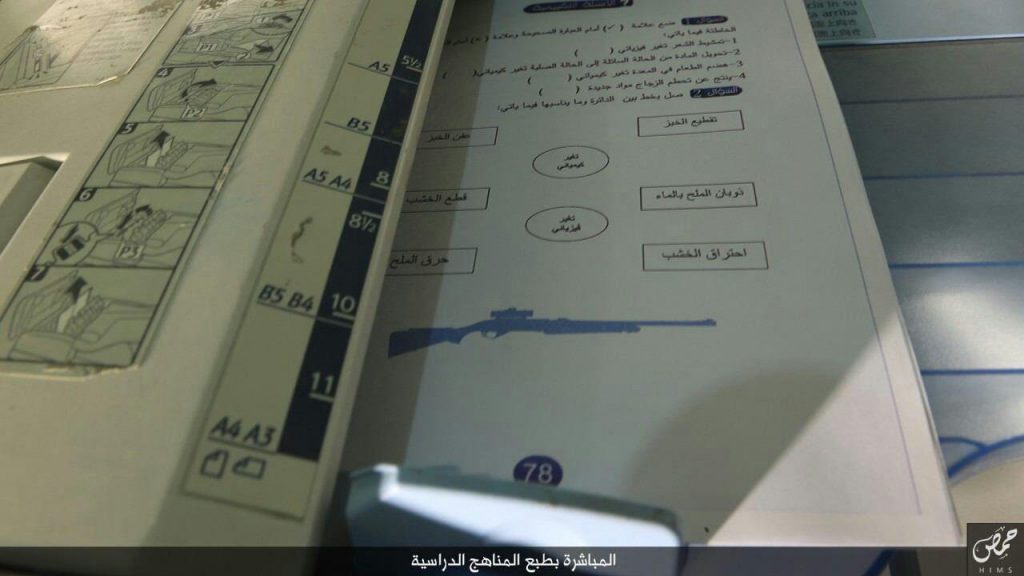

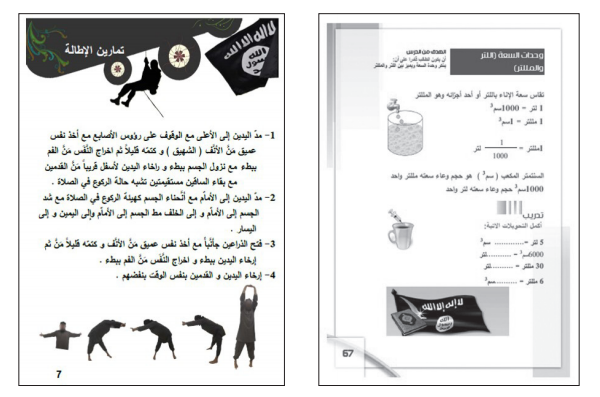

From a content point of view, it is not only a more intense religious teaching (children learn to recite from the Quran and the Hadiths, mostly sections and quotes that Islamic State uses to justify their existence and operations), that has emerged, but also a specifically designed world view stretching over and incorporated in many subjects. Take for instance Geography, which is being taught from a vastly different point of view from schools in the West, with the Islamic State Caliphate in the center, erasing the Sykes-Picot borders of the Middle East, just as the ideological and military warfare suggest. Mathematics are taught rather traditionally, however with illustrations of tanks, guns and or explosive devices – hence: logic reasoning is integrated with stories of warfare. And this might be one of the key issues to recognize, how the rhetorical forms of appeal are so strictly intertweened. How logics combined with both emotional pathos and trust (ethos) in a repetitive manner, promoted under the discourse of religious obligation enforced by Islamic State on all levels, becomes such a powerful tool leaving children without chance to oppose or challenge in their path to adolescence.

Another example is when one of the propaganda outlets (‘Library of Zeal’) released an Android application (‘Huroof’) aiding children to learn the alphabet and Arabic language. In the application the educational core is heavily influenced by ideology and jihadist themes. As The Long War Journal reported, “The app has games for memorizing and how to write the Arabic letters in addition to including a nasheed (a cappella Islamic songs) designed to help teach the alphabet. The lyrics in the nasheed are littered with jihadist terminology, while other games within the app also include militaristic vocabulary with more common, basic words. Words like “tank,” “gun,” and “rocket” are among the first few taught within the application.”

Considering my statement above about the integration of rhetorical elements, this example accentuates even further how also forms of media are closely linked to each other when using songs, lyrics, words – all creating a sense that the basic foundation of understanding (language), war and jihad, together constitute an entity and essence of life itself.

Preparations for physical fighting and military warfare is highly important as well. The older the children becomes, the more weapon skills and training-camps are involved. But at the younger ages this physical preparation in class is usually performed as a play, a game. Children perform exercises based on improving their endurance, cooperation and sense of obedience, strongly connected to the overall ideology of Islamic State emphasizing duty and obligation to take part in their war. Even here the element of singing is an important part, as children during (non-violent) exercises are asked to sing the ‘ba’yah’: the allegiance pledge to Caliph al-Baghdadi. So even if there at the youngest of ages are mainly non-violent exercises and only playful military training, it still provides the foundation of future such elements, including and combining physical preparations with concepts of loyalty to the Caliph and the state itself.

In addition and finally, exposing children to violence, desensitizing their minds and emotional investments, is crucial. In many execution propaganda-videos it is more a rule than an exception to see small children at the front of the crowd watching public executions on squares or the streets of Raqqa or other Islamic State controlled cities. In a few videos so far adolescents from the crowd watching are asked to volunteer to be executioners, and out of several volunteering a handful is picked to hold the gun or the knife. As have also been reported heavily, even I wrote about it here, many of the more high-production-value videos (hence with a global audience) of torture and executions, include children as young as 6-8 yo acting as executioners. This has an interesting anthropological value of loyalty and is part of an internal hierarchy and identity formation, making the child/adolescent climb in ranks by taking part in an execution (there is a symbolic value in cutting off the head of an apostate as it in a spiritual and symbolic sense means the child simultaneously cuts off his own potentially apostate-influenced or westernized mind and makes a complete break from the path of hypocracy and disbelieving) – thereby signifies there is no return from here on.

There are numerous more and interesting aspects to consider when it comes to the systematic indoctrination and educational system of the Islamic State, far too many. But what can we learn simply from the aspects described here?

People are never as dangerous as when they are in complete conviction about themselves being right. And the Islamic State has proven highly successful in implementing the notion of superiority and rightness through their ideological framework, not least among the younger generations. There are offline- as well as online/digital indoctrination strategies which by the Islamic State are considered fundamental in achieving this. The educational system goes beyond the classroom teachings and the Ministry of Education is closely linked to the Ministry of Media, collaborating on how different forms of media can aid the process of preparing children to forcefully become the next generation of fighters, boys growing from ‘Cubs’ into ‘Lions’.

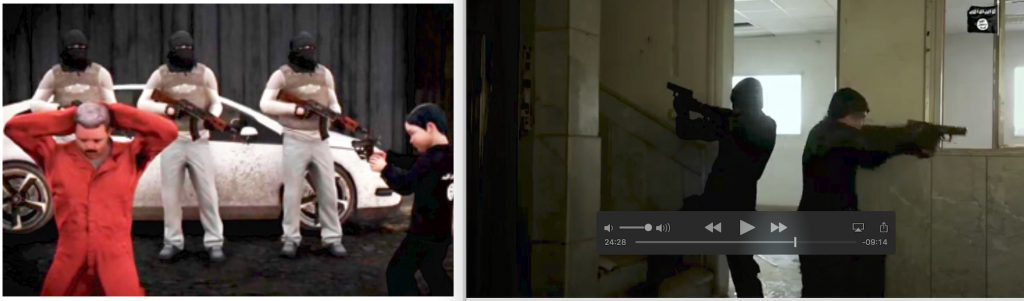

There are several mediation processes and practices in Islamic State educational efforts in general, and in this collaboration in particular., that we need to approach from a more holistic point of view than has been made so far. From mobile applications deploying a playful understanding of warfare (framed in an educational context), to images and texts in more traditional forms of curriculum textbooks filled with visual illustrations, to video-games and other applications with further enhanced information value. Finally we should include a massive output of propaganda videos which effectively, just like educational applications, blur the boundaries between reality and fiction. Videos of children acting as if they are part of a game, imitating both movements and first-shooter perspectives recognizable from any computer-game, ending up with a real killing/execution of one or several ‘apostates’, all forced to take part of the enactment. These videos are then not only circulated online, but continously screened in mobile media kiosks within the Caliphate where children and older population are viewing together.

One of the biggest mistakes of the western world in recent years has been to underestimate the long term formation of Islamic State’s ideology and state, military capabilities and brutality. By learning from this mistake we must now increase and share knowledge about the issues above, collaborate on preventive measures and find ways to deal with the upcoming and long-term threat towards western societies, but maybe even more important a major social development dimension in the region with a growing generation of children who have lived under Islamic State ruling and indoctrinating tentacles of “education”.

“Complete victory is coming – just not any time soon”

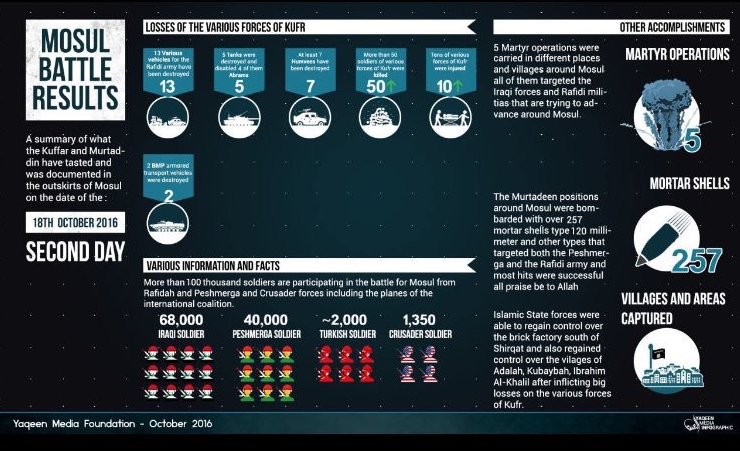

The headline quote is not only an extract from the most recent issue of ISIS magazine Rumiyah, but also a clear illustration of a shift of focus in their messaging. As the symbolically important city of Dabiq was lost for ISIS last month, the place which was prophetically announced as the place for the apocalyptic battle from which ISIS would prevail – the first incarnation of a less aggressive and more bouying-of-morale emphasis in their propaganda was visible.

Pre- The Conference talk

Next week I will attend and speak at The Conference 2016 here in Malmö, one of the world’s leading conferences on media, technology, culture and business. It gathers practitioners from a wide variety of disciplines as well as academic researchers who are interested in the continuously evolving and rapidly developing field of the creative industry. I have been kindly invited to give a talk under a session of extremist communication, in which I will present extracts of the the scope of narratives within ISIS messaging and propaganda. I will go beyond the media headlines of brutality and gruesome beheadings and tell a story about how completely opposite rhetorical appeals were implemented in the beginning of ISIS expansion and how they managed to get a historical influx of foreign fighters to the self-declared caliphate.

My hope is to show how ISIS ideological and mediated strategies differ from earlier and similar jihadist groups (especially AQI from which it derives) but also attempt to discuss how the current geographical setbacks for ISIS are reflected in their media strategies and shows a change of focus as the loss of important/strategic cities in the region is increasing.

I deeply look forward to take part of The Conference and grateful to be able to convey my insights about ISIS – an organisation with an extreme and sophisticated propaganda and ideology that I have devoted several years to in order to comprehend.

Beyond cruelty, Beyond Syria

Livestream of ISIS branded violence? Never.

A few days after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen gave a press conference about his recent work and was asked about the horrific events in relation to some of his pieces. He famously then called the attacks ”the biggest work of art there has ever been”. For this he received instant and harsh criticism, even if a more careful deconstruction of his longer answer revealed a far from simplified aesthetic and positive notion of the events. In any case, his insight is currently useful in any attempt to understand contemporary terrorism in general, and ISIS in particular.

The spectacle that was 9/11 played out in front of a global audience through television news networks, reproduced through various visual media for years to come. The objectives for this theatrical strategy are not hard to grasp. Nor is it stretching to claim there is a dominant theory of present terrorism; a theory based on a carefully considered adaptation of our neo-liberalist mechanisms of western society. Mainly this focus on attention seeking with a good message, influencing people through promoting a certain feeling within its audience, and market a brand of its organization. The enterprise of violence and socially mediated terrorism of ISIS hold several of the features aligned with successful players on the financially profit-driven market of consumptionism and the wider trade of goods and services. Witnessing ISIS still rather unique packaging of barbarism and terror in a theatrical and sophisticated form, I believe suggests a need to more extensively use terms like ’commodification of violence’ to understand the endeavours of this particular group. By adapting to a terminology deriving from marketing and commodity culture, we can perhaps more adequately and efficiently approach the key mechanisms involved in ISIS greater aim to create an atmosphere of turmoil and horror, rather than focusing solely on military advancement in and around the Caliphate. ISIS uses modern technologies in line with any other enterprise to market itself and build a relation to its audience. The commodification and marketing of violence however deviate in some important aspects, especially when it comes to audience control and trending technologies.

The Message

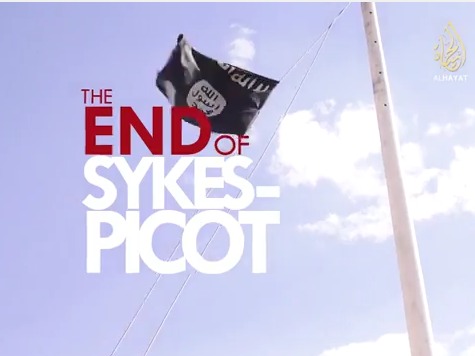

A core principle in marketing is to have a good and strong message. And let’s be honest, they do. It is not simply about inspiring an alienated youth to join any random terrorist organization, a pursuit that usually requires living underground in obscured parts of the world and from time to time conducting attacks. No, there is a larger cause at play here. ISIS is attempting to rewrite history. A far more ambitious and existential goal than held by its predecessors. Their own history, as part of a Middle East which was divided by the west through the Sykes-Picot agreement after WW1 through which countries were divided and politically aligned with western nations through different forms of agreements, is the fundamental vision to realize. They certainly emphasize this in various strands of the propaganda (The End of Sykes Picot).

To support this message when conveying it, they have a physical space (the Caliphate) and amplifiy that space through dimensions and narratives which uphold its mythical existence, including violence, belonging, brotherhood, religion etc. Compared to other groups, say Jabhat-Al Nusra, ISIS use of social media platforms to distribute messages are far more effective. Other groups try, use similar tactics, but have no real space, no coherent message but rather express ideological notions, justifications of operations and spread violence as a mean to separate themselves from other rivalry groups. In addition, ISIS hold the advantage of a significantly larger network of followers, hence also a larger network of carriers of their message. It is impossible, and not very smart to be honest, to generalize about global jihadists online, as recruits, supporters, central commands and core believers are not only vastly different in terms of individual preferences but also collectively fragmented in regards to group affiliations. In relation to this ISIS has managed to gather followers and function like a community and identity strengthening ‘help-desk’, 24/7, where followers easily find someone ot ask questions or advice, ideologically likeminded get together in groups in more or less closed chatrooms, talking about their common denominator, amplifying it and contribute to convey the strong message online. Social media platforms are, by nature, designed to be used by and attract likeminded, a fact that seemingly quite often has been neglected in terms of developing counter campaigns online (I wrote for instance about US State Department previous campaign Think Again Turn Away here).

Live or choreographed violence?

Now let’s consider a vital part of this message that ISIS embodies both physically and virtually and put it in relation to the technological strategies of enhancement: the mediated commodification of violence. We can, with advantage and in line with Stockhausen, define terrorist activities in the global network age as ’performance acts’, just as any other commodity being produced, sold to and used/consumed by an audience. In order to make the barbaric suicide attacks of graphic executions in videos accessible, various type of social media technologies are implemented, just as a firm trust on simple western news media logic to further spread the message. The grand spectacles of, let’s say the recent bombings in Baghdad and Istanbul, get a natural afterlife in both journalistic outlets and social media networks. By nature these type of attacks are spectacular to its form and also works well in selling news. The official execution videos, exhibiting orgies of graphic torture and murder, are choreographed, rehearsed and edited to promote a specific feeling among the audience and provoce a certain response from adversaries, hence strategically produced with a specific purpose.

But what about the random so-called ’inspired’ attacks carried out by minor cells or individuals? These manifestations of the influence and more or less ideological reach of ISIS share a far more uncontrollable relation to the mediation process. First of all they are more loosely connected to the organization itself and sometimes not at all aligned. Second, they are rarely part of the corpus of official propaganda but rather turn up in a more sociological form of media, created and distributed by followers. The mediated representations of these attacks are thereby harder to control for the organization, which means the preferred reading of audiences are equally fragile. And this is where it becomes interesting from the comparison to the marketing perspective earlier. Because one of the most prominent trends within branding and building a relation to the audience for companies and corporations today, is to use forms of live video streaming. Services like Facebook Live and Periscope are perhaps the most frequently used platforms, also by celebrities in their daily social media activities. This technological solution and platform is however yet to be a part of ISIS official communication strategy. So far no official operation has, to my knowledge, been broadcasted live through platforms like these. Why?

In a recent article in The Atlantic, the following is described:

”One evening this month, in the French town of Magnanville about 35 miles outside of Paris, Larossi Abballa, a 25-year-old Moroccan Frenchman, ambushed an off-duty police officer outside his home and stabbed him to death. He then broke into the house and murdered the officer’s wife with the same weapon. Minutes later he recorded himself live on Facebook with his phone, boasting of his deed and declaring his allegiance to ISIS. A police SWAT team stormed the house and fatally shot Abballa, but his image and voice lived on: ISIS’s Amaq news agency, which described Abballa as an “Islamic State fighter,” later uploaded to YouTube an edited version of the live video.”

Even if the attack itself wasn’t broadcasted, the example is still interesting and justifies the question of why the live mediation of the atrocities being carried out both by ISIS and in their name, are not implemented? Wouldn’t that be the perfect performance act for groups like ISIS?

No.

And I believe one of the most important factors behind this lies in the emphasis of audience control and branding. Live streaming of an attack or individual killing may generate more immediate shock reactions, but it has less of a long-term effect (dehumanizing victims, glorifying and justifying the violence) sought by atleast ISIS official central command. Live streaming creates a different relation to the audience in comparison to the choreographed brutality, the rehearsed and directed acts of violence that characterize the hundreds of videos that has been released as official productions of ISIS and its wilayat media wings. Killing must be produced as effortless and smooth, and a live streaming of this would not only risk to humanize victims, but also ruin the post-production advantages of editing and brushing the horrific images to control the response/effect on the audience. Along with obvious security reasons (a livestreamed killing may potentially and unintentionally reveal details of location and people) this seem to, atleast so far, been more important than the immediacy and uniquness of live killing. Everything about ISIS has up until today been characterized by strictness, control, portrayed strenth and determination. They will continue to minimise the risk of loosing that image.

Terrorism is sometimes described as mindless, senseless and irrational violence, which is totally a misconception. Of course there are exceptions throughout history, just as there are hard-defined acts of terror by individuals who later proven to have been more or less irrational. However there is no reason to believe that ISIS, no matter how desperate they are becoming on the battlefield, would loose the strong audience control in its messaging in the near future. They have developed their communication strategies for too long and they evidently still show ability to evaluate and resist certain trends and technologies for an immediate effect or attraction that would not serve their long-term purpose.

Reversal of mediated brutality

There are trajectories and trends in the media messaging of extremist groups emerging. Trends of use, narratives and purposes. Every day I work with and try to monitor these trends. Recently I have seen an interesting reversal of the strategies most closely connected to Al Qaeda and in particular ISIS. And even if there are more immediate and important human tragedies and brutality to consider, for a media scholar like myself it is of huge importance to also see how the operations and tactics in the conflict are communicated through various type of media platforms.

As the military interventions against mainly ISIS unfold in the region, local militias and resistance groups are advancing their geographical reach and succeed to obtain territories and cities previously under ISIS control, most recently the city of Palmyra. Much of the attention (as in mainstream western media) around this have focused on the symbolic loss for ISIS, the strategic win for militias and security forces fighting the brutal organization. But, a backdrop to all this, which for different reasons is not very well known (yet), is the strategic adoption of ISIS methodology from these groups who manage to win and fight them on the ground. As ISIS still is keen on mediating its entire machinery of military operations as well as deadly treatment of its prisoners, now this mediation tactic of exhibiting a position of strength is also played out by the opponent side. Videos and pictures have started to appear online showing Shiite militias and member of the Iraqi security forces killing and mutilating bodies of their ISIS fighters held captive or captured on the battlefield. Carefully should we approach this type of media material, and there are a great number of videos that are not genuine, but nevertheless they are significant in understanding where the role of media in contemporary conflict is heading. Here is just one example.

Instagram later chose to delete this account where holders of the social media account requested its followers to vote about the fate of the captured ISIS member. It stated: “You can vote For (kill him or let him go) You have one houer to vote We will post his fate after one houer Tag your friends and take your right take your reveng from isis right now. Please we dont have the time just one houer so tag your friends,”

This particular incident has though been questioned in terms of its veracity, however it is not an isolated example. Nor is it solely done with a purpose of retaliation and post similar brutality, but an expression of an increasingly growing counter-propaganda strategy with a purpose to deconstruct the powerful narrative that ISIS has produced and disseminated for several years trying to manage its visibility and enforce a perception of a strong and ever expanding state.

It is without a doubt a frightening development where the actions of achieving this is mediated, involving global audiences and only escalates an already devastating conflict in the countries where ISIS have managed to establish provinces (wilayats). One would think that the media strategies of ISIS would be seen, tragic as it may sound, as unique. But also isolated examples of modern terrorism. Unfortunately, I fear their strategies are turning into mainstream even for those who oppose them.

Why our beloved children?

The role of children in contemporary islamist extremism is a topic of debate for different reasons. And rightly so. It is of great significance to include aspects of using children in psychological warfare, as children have a symbolic value and rhetorical appeal in extremist communication and propaganda. And there are several dimensions in which children tragically have been put in the spotlight when violent ideologies are turned from theory to practice and leaves nothing but grief and fear behind in its path.

The devastation escalates. Our hopes for any form of breathing space or even short-term resolution are put on hold. This week we have seen horrific suicide attacks in for instance Belgium, Iraq and Pakistan. These attacks share similarites and differences. Beyond them there are numerous others, especially in countries like Syria, Iraq, Libya, Nigeria. Every attack is a tragedy in itself.

But there is something about this past week that strikes me. Something you don’t have to be a parent to relate to. And that is the fact that recent attacks seem to strategically target children or young people (like the bomb at a soccer stadium outside Baghdad a few days ago, and yesterdays devastating blast at a playground in Lahore).

We are witnessing an increase of targeting children in spectacular attacks, often carried out by suicide bombers. The psychological mechanisms behind these type of attacks is not for me to speculate on. However considering my knowledge and experiences of researching messaging and propaganda of groups within the global jihadist movement, there are evident links between the ideological warfare and the operations on the ground.

Children are victims. And sadly they play an important role no matter from which angle you observe. As I have written about before, they are increasingly depicted in propaganda underscoring and satisfying several narratives. They are symbols of a future. Symbols of purity. As several islamist terrorist groups are millenarian (in various degree) sharing apocalyptic visions and utopias, children become equal to survival for the group and its core ideas. For instance, they are portrayed in ISIS proapaganda both as happy and peaceful (as a way to attract women/mothers to join the Caliphate and be a part of building a future beyond the current conflict), and they are also portrayed in combat and training situations as well as at school studying, illustrating lojalty, determination and conviction as a mean to strengthen the overall notion that the Caliphate will be the stakeholder surviving the apocalyptic battle of our time. Young children have recently also been used as executioners in several brutal videos coming out os ISIS media industry.

Simultaneously, children are important symbolic targets when carrying out attacks against non-believers. Christians, shia muslims, opponent sunnis – it is of minor importance. As long as an attack gets both immediate attention and effect (fear, chaos, political reaction) and symbolic value (strength, mercyless, no future for adversaries) there are tragically several reasons why children and women are potentially high profile targets. So when the bomb blasted next to a plyground, full of Christian women and children celebrating Easter in Lahore yesterday, it was not only an attack from an islamist group trying to provoce the Pakistani government and spread fear. It was also a symbolic attack with religious connotations, targeting the most vulnerable and beloved of human beings; children.

(AFP Photo/Arif Ali)

I wish I could say I believe these attacks were isolated.

I wish I could say that studying the messaging and propaganda of this groups gives me hope to believe children will not be targeted again.

I really wish I could.

But I can’t.

And that is an insight that no matter its importance for predicting which path current islamist extremism will follow, breaks my heart to realize.

I guess what we all can do is to spoil our children, in every way we can. Provide them with love and care.

And share thoughts to those who no longer have a child to spoil.