Livestream of ISIS branded violence? Never.

A few days after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen gave a press conference about his recent work and was asked about the horrific events in relation to some of his pieces. He famously then called the attacks ”the biggest work of art there has ever been”. For this he received instant and harsh criticism, even if a more careful deconstruction of his longer answer revealed a far from simplified aesthetic and positive notion of the events. In any case, his insight is currently useful in any attempt to understand contemporary terrorism in general, and ISIS in particular.

The spectacle that was 9/11 played out in front of a global audience through television news networks, reproduced through various visual media for years to come. The objectives for this theatrical strategy are not hard to grasp. Nor is it stretching to claim there is a dominant theory of present terrorism; a theory based on a carefully considered adaptation of our neo-liberalist mechanisms of western society. Mainly this focus on attention seeking with a good message, influencing people through promoting a certain feeling within its audience, and market a brand of its organization. The enterprise of violence and socially mediated terrorism of ISIS hold several of the features aligned with successful players on the financially profit-driven market of consumptionism and the wider trade of goods and services. Witnessing ISIS still rather unique packaging of barbarism and terror in a theatrical and sophisticated form, I believe suggests a need to more extensively use terms like ’commodification of violence’ to understand the endeavours of this particular group. By adapting to a terminology deriving from marketing and commodity culture, we can perhaps more adequately and efficiently approach the key mechanisms involved in ISIS greater aim to create an atmosphere of turmoil and horror, rather than focusing solely on military advancement in and around the Caliphate. ISIS uses modern technologies in line with any other enterprise to market itself and build a relation to its audience. The commodification and marketing of violence however deviate in some important aspects, especially when it comes to audience control and trending technologies.

The Message

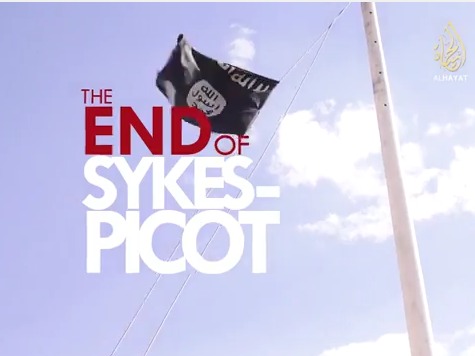

A core principle in marketing is to have a good and strong message. And let’s be honest, they do. It is not simply about inspiring an alienated youth to join any random terrorist organization, a pursuit that usually requires living underground in obscured parts of the world and from time to time conducting attacks. No, there is a larger cause at play here. ISIS is attempting to rewrite history. A far more ambitious and existential goal than held by its predecessors. Their own history, as part of a Middle East which was divided by the west through the Sykes-Picot agreement after WW1 through which countries were divided and politically aligned with western nations through different forms of agreements, is the fundamental vision to realize. They certainly emphasize this in various strands of the propaganda (The End of Sykes Picot).

To support this message when conveying it, they have a physical space (the Caliphate) and amplifiy that space through dimensions and narratives which uphold its mythical existence, including violence, belonging, brotherhood, religion etc. Compared to other groups, say Jabhat-Al Nusra, ISIS use of social media platforms to distribute messages are far more effective. Other groups try, use similar tactics, but have no real space, no coherent message but rather express ideological notions, justifications of operations and spread violence as a mean to separate themselves from other rivalry groups. In addition, ISIS hold the advantage of a significantly larger network of followers, hence also a larger network of carriers of their message. It is impossible, and not very smart to be honest, to generalize about global jihadists online, as recruits, supporters, central commands and core believers are not only vastly different in terms of individual preferences but also collectively fragmented in regards to group affiliations. In relation to this ISIS has managed to gather followers and function like a community and identity strengthening ‘help-desk’, 24/7, where followers easily find someone ot ask questions or advice, ideologically likeminded get together in groups in more or less closed chatrooms, talking about their common denominator, amplifying it and contribute to convey the strong message online. Social media platforms are, by nature, designed to be used by and attract likeminded, a fact that seemingly quite often has been neglected in terms of developing counter campaigns online (I wrote for instance about US State Department previous campaign Think Again Turn Away here).

Live or choreographed violence?

Now let’s consider a vital part of this message that ISIS embodies both physically and virtually and put it in relation to the technological strategies of enhancement: the mediated commodification of violence. We can, with advantage and in line with Stockhausen, define terrorist activities in the global network age as ’performance acts’, just as any other commodity being produced, sold to and used/consumed by an audience. In order to make the barbaric suicide attacks of graphic executions in videos accessible, various type of social media technologies are implemented, just as a firm trust on simple western news media logic to further spread the message. The grand spectacles of, let’s say the recent bombings in Baghdad and Istanbul, get a natural afterlife in both journalistic outlets and social media networks. By nature these type of attacks are spectacular to its form and also works well in selling news. The official execution videos, exhibiting orgies of graphic torture and murder, are choreographed, rehearsed and edited to promote a specific feeling among the audience and provoce a certain response from adversaries, hence strategically produced with a specific purpose.

But what about the random so-called ’inspired’ attacks carried out by minor cells or individuals? These manifestations of the influence and more or less ideological reach of ISIS share a far more uncontrollable relation to the mediation process. First of all they are more loosely connected to the organization itself and sometimes not at all aligned. Second, they are rarely part of the corpus of official propaganda but rather turn up in a more sociological form of media, created and distributed by followers. The mediated representations of these attacks are thereby harder to control for the organization, which means the preferred reading of audiences are equally fragile. And this is where it becomes interesting from the comparison to the marketing perspective earlier. Because one of the most prominent trends within branding and building a relation to the audience for companies and corporations today, is to use forms of live video streaming. Services like Facebook Live and Periscope are perhaps the most frequently used platforms, also by celebrities in their daily social media activities. This technological solution and platform is however yet to be a part of ISIS official communication strategy. So far no official operation has, to my knowledge, been broadcasted live through platforms like these. Why?

In a recent article in The Atlantic, the following is described:

”One evening this month, in the French town of Magnanville about 35 miles outside of Paris, Larossi Abballa, a 25-year-old Moroccan Frenchman, ambushed an off-duty police officer outside his home and stabbed him to death. He then broke into the house and murdered the officer’s wife with the same weapon. Minutes later he recorded himself live on Facebook with his phone, boasting of his deed and declaring his allegiance to ISIS. A police SWAT team stormed the house and fatally shot Abballa, but his image and voice lived on: ISIS’s Amaq news agency, which described Abballa as an “Islamic State fighter,” later uploaded to YouTube an edited version of the live video.”

Even if the attack itself wasn’t broadcasted, the example is still interesting and justifies the question of why the live mediation of the atrocities being carried out both by ISIS and in their name, are not implemented? Wouldn’t that be the perfect performance act for groups like ISIS?

No.

And I believe one of the most important factors behind this lies in the emphasis of audience control and branding. Live streaming of an attack or individual killing may generate more immediate shock reactions, but it has less of a long-term effect (dehumanizing victims, glorifying and justifying the violence) sought by atleast ISIS official central command. Live streaming creates a different relation to the audience in comparison to the choreographed brutality, the rehearsed and directed acts of violence that characterize the hundreds of videos that has been released as official productions of ISIS and its wilayat media wings. Killing must be produced as effortless and smooth, and a live streaming of this would not only risk to humanize victims, but also ruin the post-production advantages of editing and brushing the horrific images to control the response/effect on the audience. Along with obvious security reasons (a livestreamed killing may potentially and unintentionally reveal details of location and people) this seem to, atleast so far, been more important than the immediacy and uniquness of live killing. Everything about ISIS has up until today been characterized by strictness, control, portrayed strenth and determination. They will continue to minimise the risk of loosing that image.

Terrorism is sometimes described as mindless, senseless and irrational violence, which is totally a misconception. Of course there are exceptions throughout history, just as there are hard-defined acts of terror by individuals who later proven to have been more or less irrational. However there is no reason to believe that ISIS, no matter how desperate they are becoming on the battlefield, would loose the strong audience control in its messaging in the near future. They have developed their communication strategies for too long and they evidently still show ability to evaluate and resist certain trends and technologies for an immediate effect or attraction that would not serve their long-term purpose.